What will happen in 2024?

A look back at 2023

2023 was the hottest year ever recorded, with record-breaking heatwaves and rising sea temperatures around the world. Japan also experienced extreme heat during summer, which affected agriculture, fisheries, and health. The words “global boiling” used by United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres to describe the situation attracted much attention in Japan as well. According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), the average temperature in 2023 was 1.45°C warmer than pre-industrial levels (1850–1900). This situation is becoming increasingly serious as we approach the international target of limiting the warming to 1.5°C.

In 2023, at the G7 Summit when Japan held the presidency and at the COP28 conference in Dubai (28th session of the Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change), agreement was reached to expand renewable energy and move away from fossil fuels. However, the efforts and actions of the world’s countries are still falling short of what is needed.

In Japan, the GX Promotion Act was enacted in order to promote the so-called Green Transformation (GX), and financial support for major emitting sectors is being promoted based on investment strategies. However, it is not clear how the promotion of GX will actually reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. On the other hand, efforts to reduce the use of coal remain lax. There are still many problems with Japan’s climate policy.

Outlook for 2024

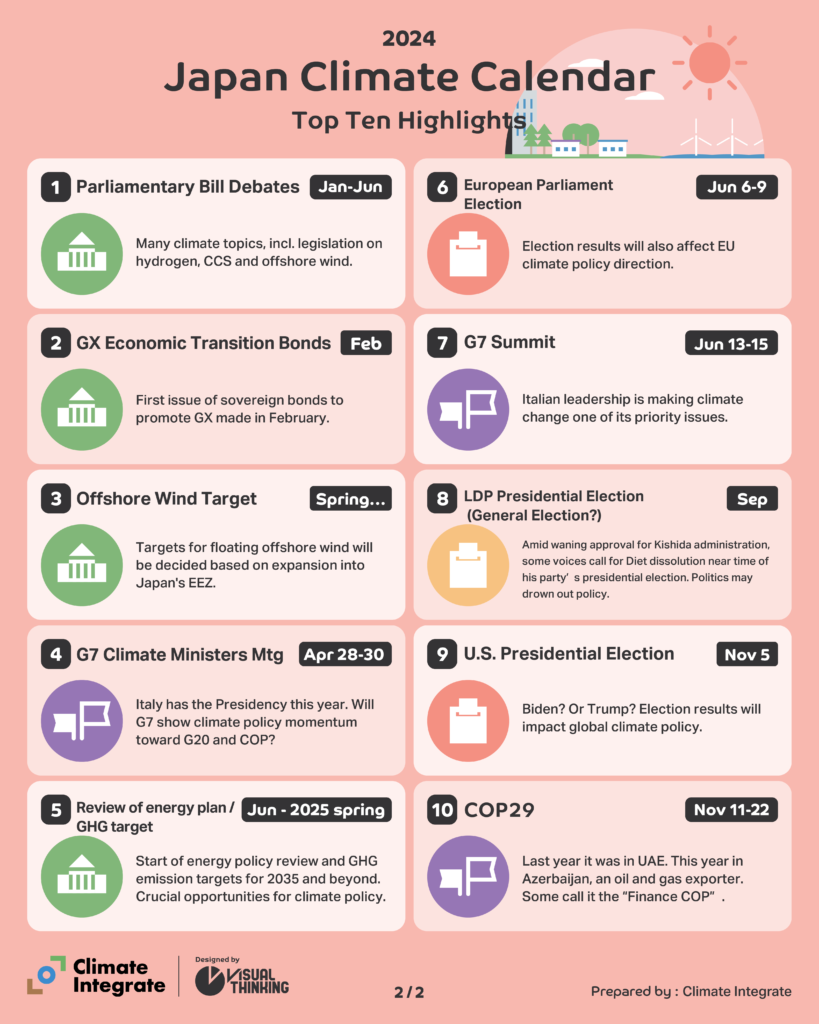

This is a major election year globally, with elections being held in about 80 countries around the world. In particular, the US presidential election in November is attracting much attention. In June, there will be a general election in India, which is now the most populous country in the world. In Japan, an LDP (Liberal Democratic Party) presidential election will be held in September. (The LDP has ruled Japan almost continuously since it was established in 1955.) If parliament is dissolved around the time of the general election, politics will drown out policy.

Whatever happens in politics, 2024 is a very important year for climate policy. For “Nationally Determined Contributions” (NDCs) to be submitted to the UN by February 2025, discussions must begin soon regarding GHG emission reduction targets for 2035 and beyond. This is also an important year to plan the path toward achieving carbon neutrality in Japan by 2050, as 2024 marks the start of the review of Japan’s energy policy (Strategic Energy Plan), done once every three years.

For GX promotion, the first GX Economic Transition Bonds (1.6 trillion yen) were issued in February. Several more issues are expected during the year. Will government support prevent the spread of corporate greenwashing? Will it accelerate decarbonization? Will it continue to promote offshore wind power and other options for renewable energy? All of these policy trends need to be monitored carefully.

Highlight Summary

Commentary

1. Parliamentary Bill Debates (until June)

Many amendments and bills have been submitted for the 2024 ordinary Diet session.

The Hydrogen Society Promotion Bill (Bill for Promoting the Supply and Utilization of Low-Carbon Hydrogen for a Smooth Transition to a Decarbonized Growth Economic Structure) stipulates that suppliers and users of hydrogen, ammonia, synthetic fuels, and synthetic methane are to receive funding and subsidies to bridge the price gap with fossil fuels in order to promote hydrogen, which comes at a higher cost. The problem is that the term “low-carbon hydrogen, etc.” makes no distinction between hydrogen produced from fossil fuels and hydrogen produced from renewable energy. Unless a proper distinction is made, the legislation will actually be promoting hydrogen derived from fossil fuels. Another problem is that the legislation would promote the use of hydrogen in sectors where the direct use of renewable energy would be price competitive, including mobility and the electricity generation sector.

The CCS Business Bill (Carbon Capture and Storage Business Bill) prepares the business environment for storing CO2 underground, with a notification and approval system for businesses transporting, drilling, and storing CO2. Measures to store and dispose of CO2 underground are being given the priority, while measures to significantly cut emissions from thermal power plants (fossil fuel combustion) and other major sources are not adequately introduced.

To expand the deployment of offshore wind power turbines beyond what is currently permitted (ports and territorial waters) to include Japan’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), an amendment bill to expand offshore wind to the EEZ (Bill to Partially Amend the Act on Promoting the Utilization of Sea Areas for the Development of Marine Renewable Energy Power Generation Facilities) provides for the national government to designate target areas, establish stakeholder councils, and approve projects that satisfy certain criteria.

A draft amendment to the Act on Promotion of Global Warming Countermeasures has provisions to establish a system to designate an entity responsible for implementing the Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM).

2. First Issue of GX Economic Transition Bonds (Feb)

Under the GX Promotion Act, the government has a policy of making upfront investments in priority areas, and in February 2024, released its first issue of GX Economic Transition Bonds (Climate Transition Bonds), totaling 1.6 trillion yen in 5-year and 10-year bonds. Ammonia co-firing with coal-fired power generation was not included among technologies targeted for GX-related investment in the first bond issue, a possible sign that the government did consider criticism from institutional investors.

3. Target-Setting for Offshore Wind (Spring…)

Among all countries of the world, Japan is endowed with some of the best offshore wind power potential, and expectations are high for expanded deployment in the coming years. Project development is already under way for bottom-fixed offshore wind power, but going forward, the government is planning to expand deployment of floating offshore wind turbines in Japan’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Offshore wind power generation is a key to Japan’s energy transition and an opportunity to foster new industries.

4. G7 Ministers’ Meeting on Climate/Energy/Environment (Apr 28-30)

Italy has the presidency of this year’s G7 Summit. If we are to achieve the 1.5°C Paris target, this G7 will be an important opportunity for developed countries to get more specific about goals agreed last year at COP28 to “triple renewables,” “double efficiency” and “transition away from fossil fuels.” At the G7 meeting hosted in Japan last year, the Ministerial Meeting on Climate, Energy and Environment discussed environment and energy in an integrated manner, and this serves as a forum for substantive consensus building on climate change. This year as well the Ministerial Meeting can be expected to set a tone for the leaders’ summit in June.

5. Review of Strategic Energy Plan and GHG Emission Targets (Jun – spring 2025)

Japan’s Strategic Energy Plan lays out the nation’s energy policy and is revised every three years in accordance with legislation. The year 2024 will mark the start of the next review cycle, which will look at Japan’s energy situation for 2030 and beyond. Key points will be to realize a policy transition by placing a priority on reducing the use of coal and LNG in the electric power sector and significantly increasing renewables, promoting electrification in the heating and transportation sectors, and promoting the use of green hydrogen in sectors where electrification is difficult. The challenge for Japan will be to wean itself off systems based on thermal (fossil fuel) and nuclear power and create a new electrical power system.

On the international scene, Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) must be submitted to the United Nations every five years, and the next deadline is in February 2025. In the NDCs, countries are required to articulate their GHG emission reduction targets and the policy measures intended to achieve them. Since Japan has already committed to a target for 2030, it must now decide on reduction targets for 2035 and 2040, and decide on policy measures. Since about 90% of Japan’s CO2 emissions are derived from energy, discussions on the Strategic Energy Plan and GHG emission reduction targets are expected to proceed in tandem. However, the political situation this year makes it difficult to predict the timing of discussions.

6. European Parliament Election (Jun 6-9)

The EU is a key player in international climate negotiations, and has adopted the European Green Deal to promote decarbonization integrated with economic policy. In February, the European Commission recommended a 90% reduction in GHG emissions in the EU by 2040 based on the European Climate Law, and related legislation is being prepared for submission by year end. This initiative will gain momentum if the parliament is united, but could be slowed depending on its composition.

7. G7 Summit (Jun 13-15)

The next G7 leaders’ summit will be held in Apulia in southern Italy . This year’s summit will again focus on responding to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but climate change and food issues are also important themes. Last year, G7 discussions focused on issues such as the phase-out of domestic unabated coal power generation, decarbonization of the power sector by 2035, ending public support for the international unabated fossil fuel sector, and the realization of 100% zero-emission vehicles. Leadership from developed countries is crucial to keep the global target of 1.5°C within reach, and agreement at the G7 is an important touchstone for the G20 and COP29 agreements.

8. LDP Presidential Election (Dissolution/General Election?) (Sep)

The Kishida administration has been facing plummeting approval ratings due to various scandals and revelations of political slush funds. There has been talk about who will be Japan’s next prime minister, and the possibility of dissolution of parliament and general election before year end. Needless to say, the political situation is uncertain. As described above, this is a critical year on many fronts from the perspective of climate and energy policy, with debate about Japan’s NDC and Strategic Energy Plan, and important events such as the G7 Summit. There are concerns that political attention will focus only on political affairs.

In the event of dissolution and a general election being called, to what extent will climate and energy policy become election issues, and what emphasis will each political party and candidate give them? Answers to those questions will be the key to predict the future. The intensification of climate change is shaking the security of Japan as a whole, and directly affecting the peoples’ daily lives, the economy, and employment. If voters become more interested, climate and energy policies become a priority issue and contested in the election, change may become possible. This is also an opportunity to give climate policies a boost using the power of one- voter-one-vote.

9. U.S. Presidential Election (Nov 5)

The upcoming U.S. presidential election has become a one-on-one battle between Biden and Trump. There is much debate around what happens “if” Trump is elected. The return of Trump, who as former president withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, would likely negatively affect climate policy, promote fossil fuels, and delay climate policy. Meanwhile, the Inflation Reduction Act has had positive impacts on the local economy by providing tax incentives for many domestic green industries, so some are saying the fundamentals wouldn’t change. If Biden takes office for a second term, the Biden administration is likely to go beyond even what was done during the first term in terms of driving climate policy. Top U.S. climate diplomat John Podesta, who succeeded John Kerry, has also stated that he will lay out his country’s climate policy directions in a pledge by year end. In any case, the climate crisis will not fade, so the need for stronger actions will only increase. Japan would be wise not to be buffeted about by circumstances, but to stay the course for steady progress of climate policy.

10. COP29 Climate Conference (Baku, Nov 11-22)

The 29th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP29) runs from November 11 to 22 in Baku, Azerbaijan. The COP28 meeting in Dubai last year had a record high of nearly 100,000 attendees, and reportedly the highest attendance ever by fossil fuel lobbyists. The repeated hosting of COP meetings by fossil fuel exporters has raised concerns that climate negotiations have been hijacked by the fossil fuel lobby. Some are referring to COP29 as being the “finance COP.” Tackling climate change will require finance for mitigation, adaptation, loss and damage, for the populations that live in the most vulnerable countries. At COP29, it will be important to reexamine existing funding structures and establish goals to secure sufficient and predictable funding. In addition, in preparation for the submission of NDCs, scheduled for February 2025, it will also be necessary to accelerate measures to reduce GHG emissions in each country and to close the gap with the 1.5°C target.