Japan is actively promoting the use of fuel ammonia, purportedly in an effort to achieve carbon neutrality. There are great expectations for its use as an alternative fuel to coal, particularly in the thermal power sector. Could the use of fuel ammonia really be a key to decarbonization?

Ammonia as an alternative fuel to coal?

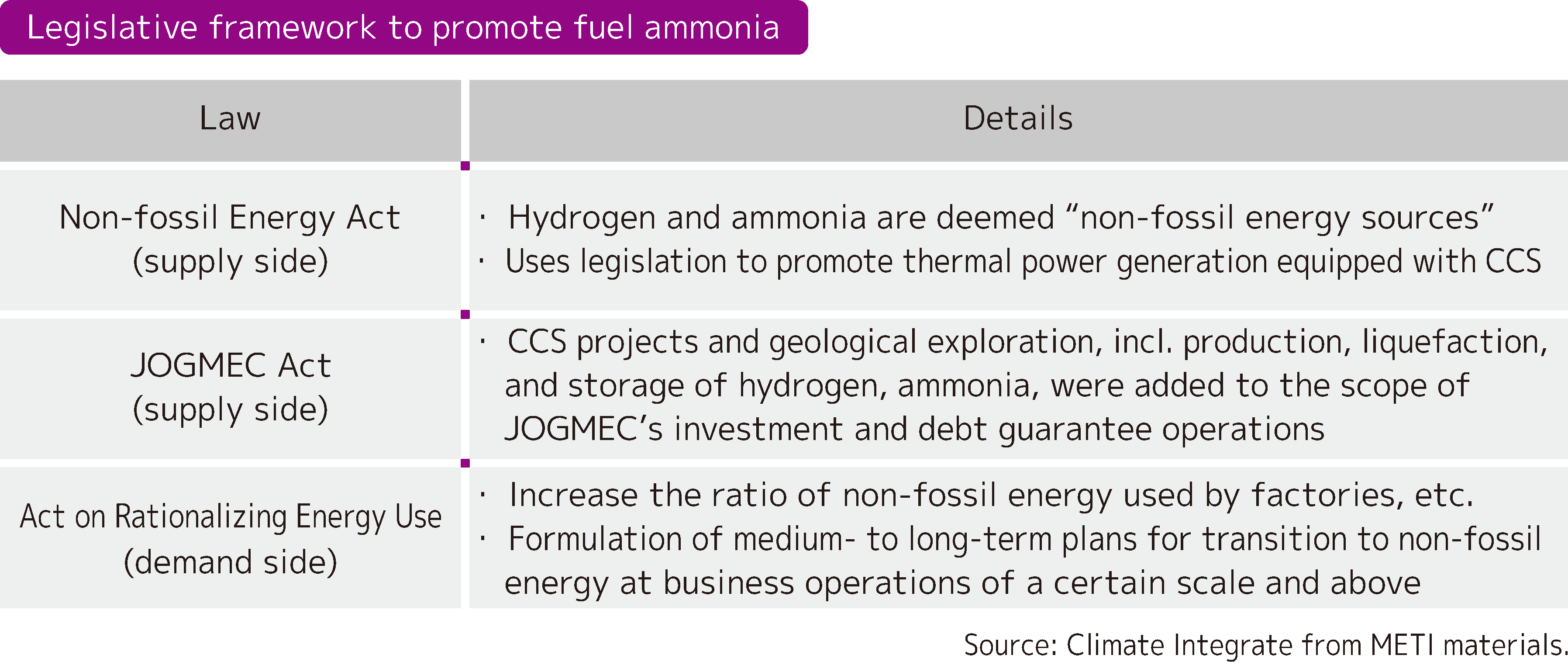

The government is giving its all-out support to expand the use of fuel ammonia with every tool available, from strategic plans, legislation, subsidies, and debt guarantees, to memorandums of understanding with Southeast Asian countries, and more. The private sector is rushing to join the bandwagon with a wave of new ventures by key players, including power utilities, trading companies, plant builders, shipping companies, and financial institutions.

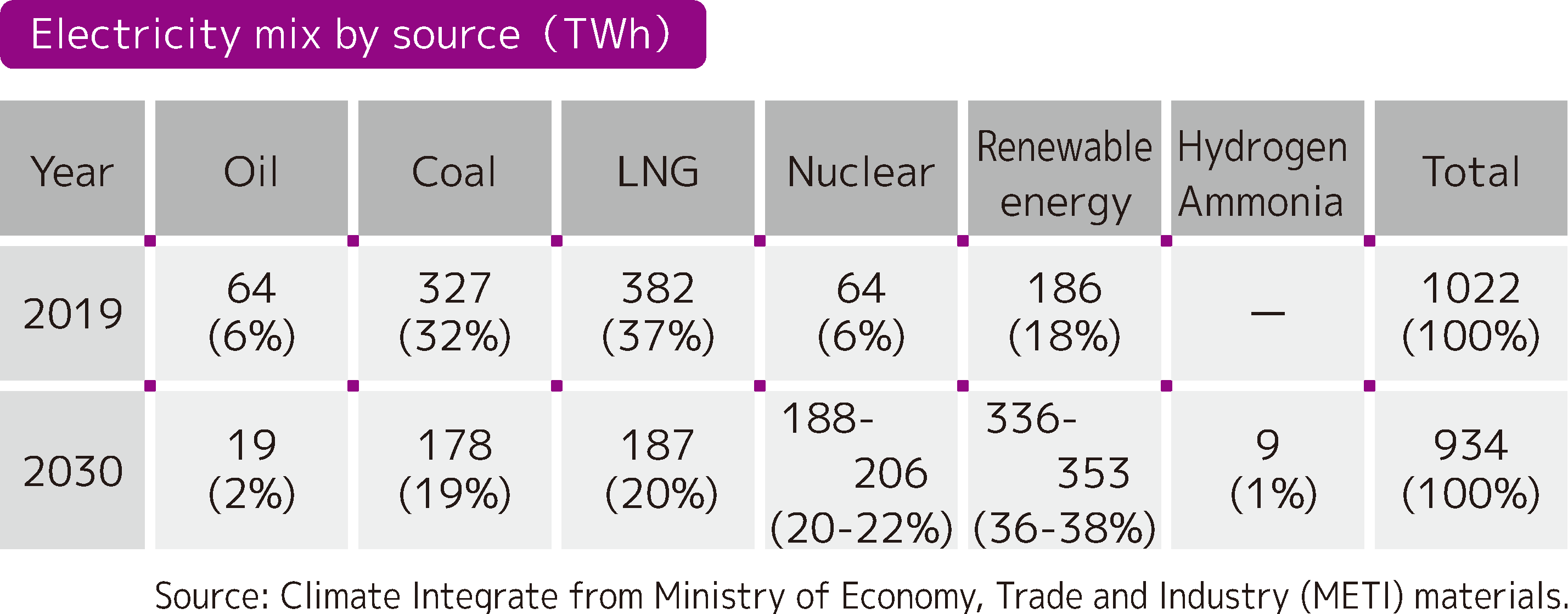

Although there are also moves elsewhere to promote hydrogen and ammonia for uses other than power generation, Japan is really the only country in the world where the public and private sectors are unified to proactively promote ammonia and hydrogen as fuels for co-firing with coal for power generation. However, despite aggressive efforts, the use of hydrogen and ammonia in the electricity mix is still projected to be no more than 1% (9 TWh) of the electricity mix in 2030. Full-scale use is not expected until 2030.

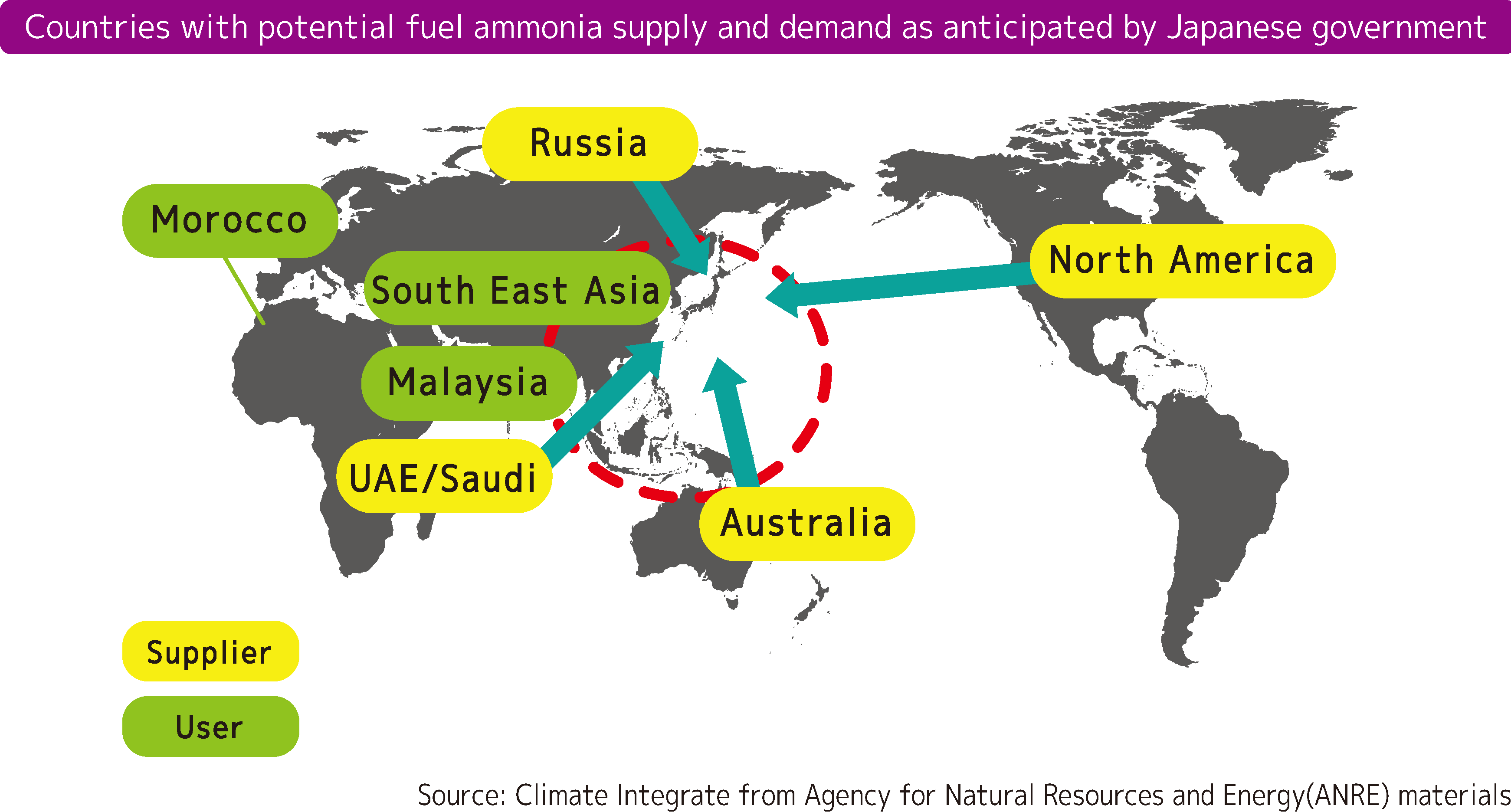

Eying ammonia’s future use as a fuel, the government expects annual domestic demand for ammonia to increase significantly from 1 million tons today to 3 million tons in 2030, and 30 million tons in 2050. The government aims to build a 100 million ton global supply chain for fuel ammonia by Japanese companies by 2050. In order to secure a supply of liquefied natural gas (LNG), the raw material for ammonia, the government is trying to further expand the use of LNG by encouraging increases in production in countries other than Russia, and this includes bolstering government involvement in support for upstream development and the procurement of LNG.

In addition, in order to create demand for ammonia, the government for the time being counts ammonia as a “non-fossil energy source” that does not emit CO2, even if CO2 is emitted when produced from fossil fuels such as LNG.

The use of fuel ammonia is also being promoted under the banner of international climate change cooperation to Southeast Asian countries, through the government’s Green Innovation Fund, Transition Finance, and public-private sector initiatives.

With this support, more than 60 Japanese companies, research institutes and government agencies have been involved in over 80 fuel ammonia projects, ranging from production, transport and storage to use in thermal power generation. The momentum behind all of this is very strong.

CO2 emission reductions, economics and environmental impacts of ammonia

The use of ammonia in the thermal power sector has several challenges, as described below.

①CO2 emission reductions

Ammonia is sometimes claimed to be “CO2-free,” “zero carbon,” “zero emissions” or “decarbonized fuel” as it doesn’t emit CO2 during combustion. However, about 1.6 tons of CO2 are emitted per ton of ammonia produced, because ammonia is currently manufactured from fossil fuels (natural gas).

In addition, as the government’s goal is to achieve 20% co-firing in coal-fired power generation by 2030, 80% of the fuel would still be coal and continue emitting CO2.

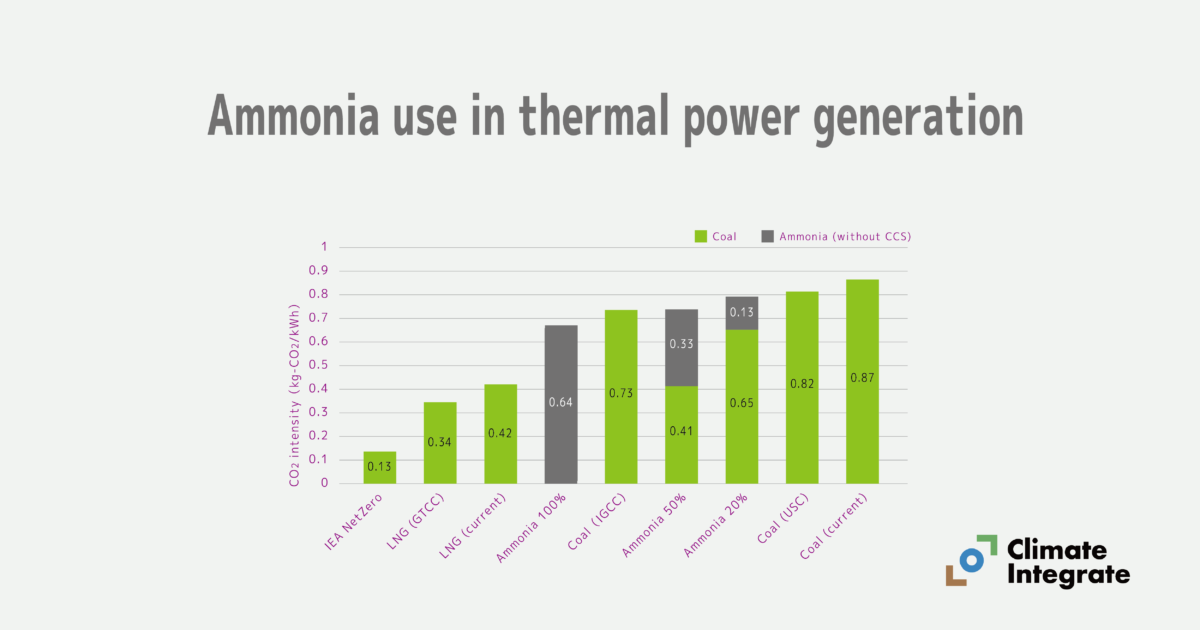

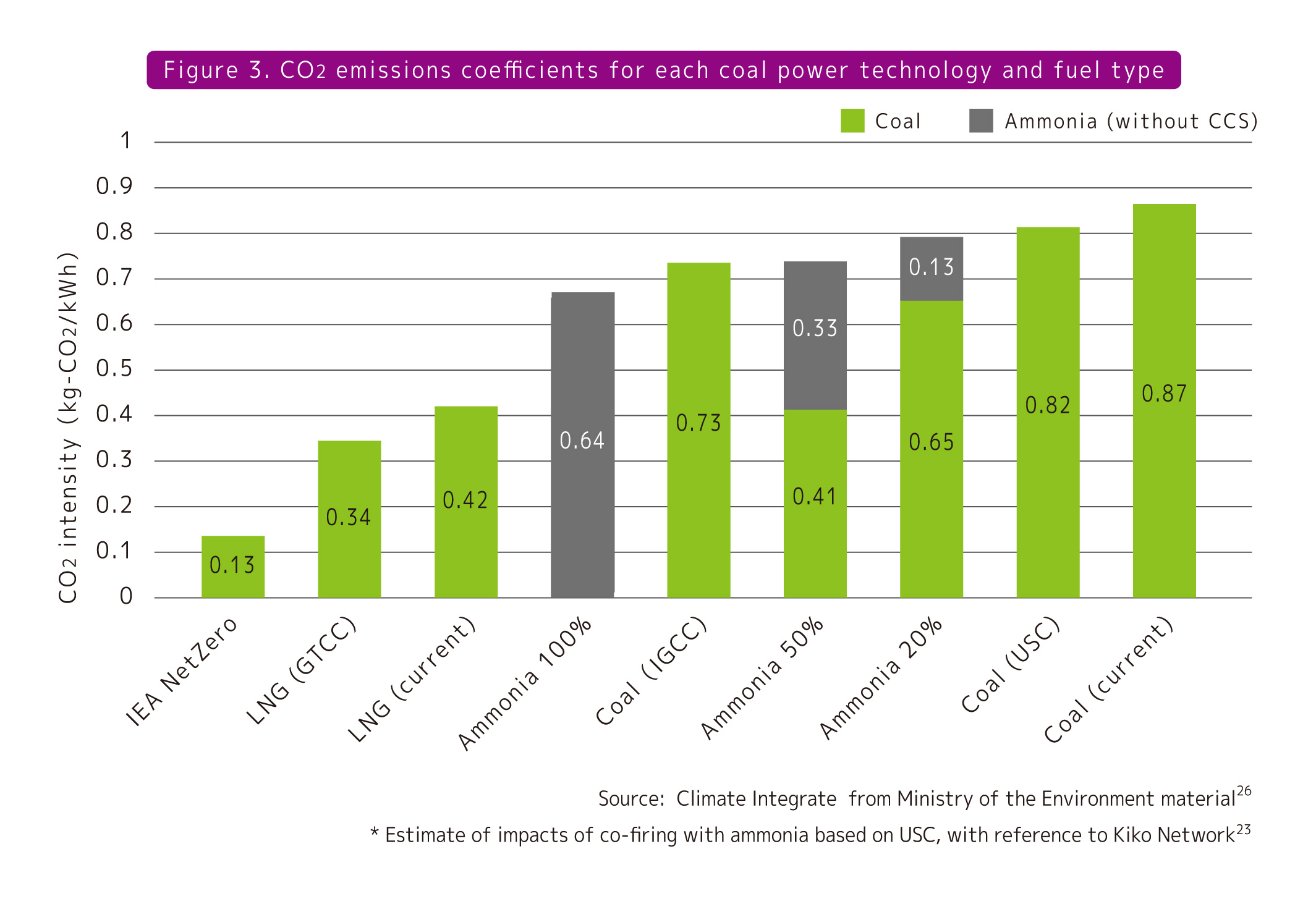

There is currently no basis in reality to declare ammonia as “CO2-free.” The next graph shows that the emission reductions by co-firing with ammonia will be negligible unless emissions from ammonia production and coal-fired power generation are abated with CO2 capture and storage (CCS). Even if 100% ammonia combustion is achieved in coal-fired power generation, it would still emit more than 1.5 times the CO2 of LNG-fired power generation.

The government is working to develop legislation with the goal of commercially launching CCS by 2030, but that goal is elusive as there are many challenges to commercialization.

②Economics

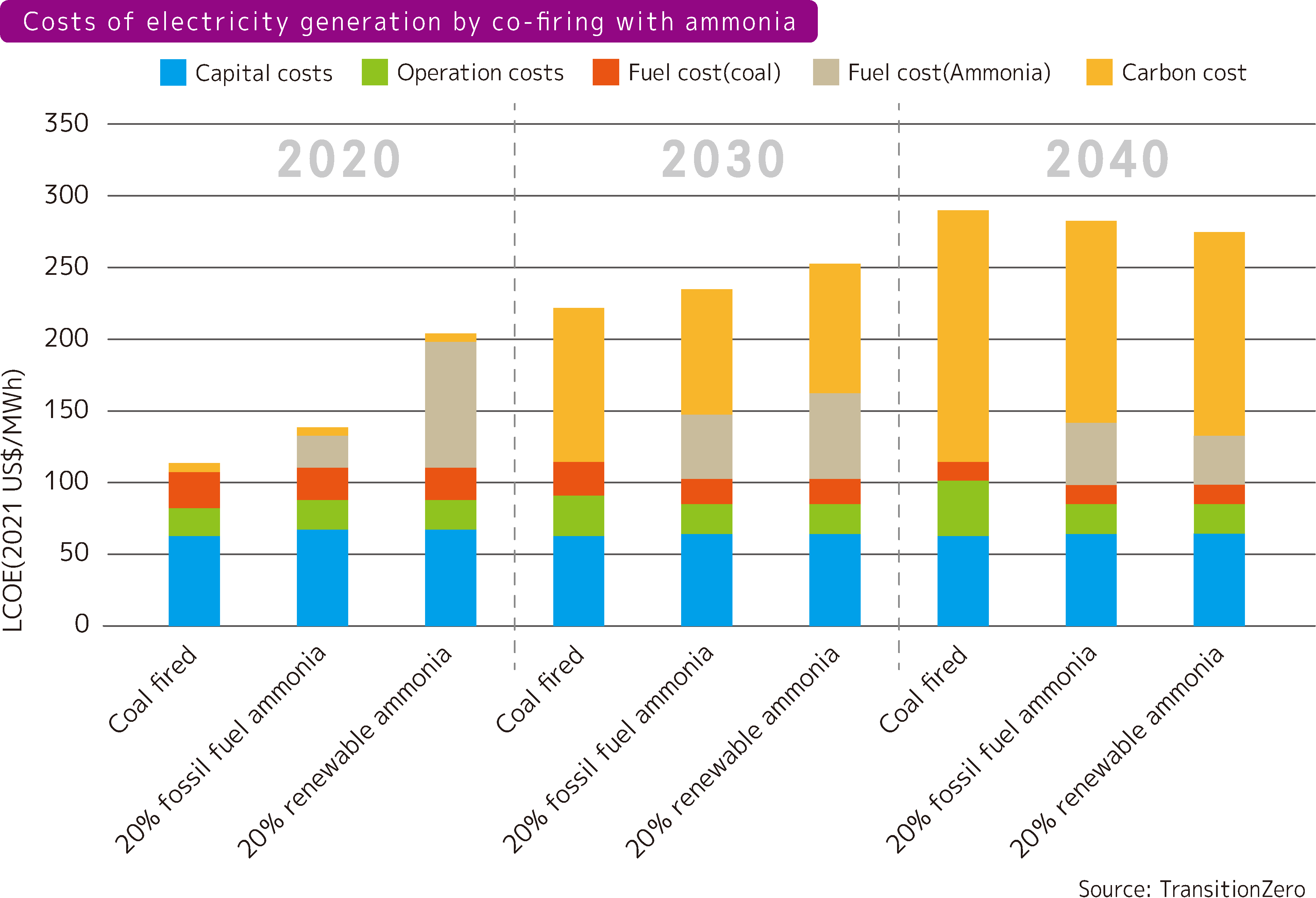

Co-firing using ammonia is more expensive than the use of coal alone. The UK thinktank TransitionZero has stated that with 20% co-firing using ammonia produced from fossil fuels for coal-fired power generation in Japan, fuel cost will be twice that of coal-firing alone. When future carbon price increases are factored in, fuel cost rises to three times that of coal.

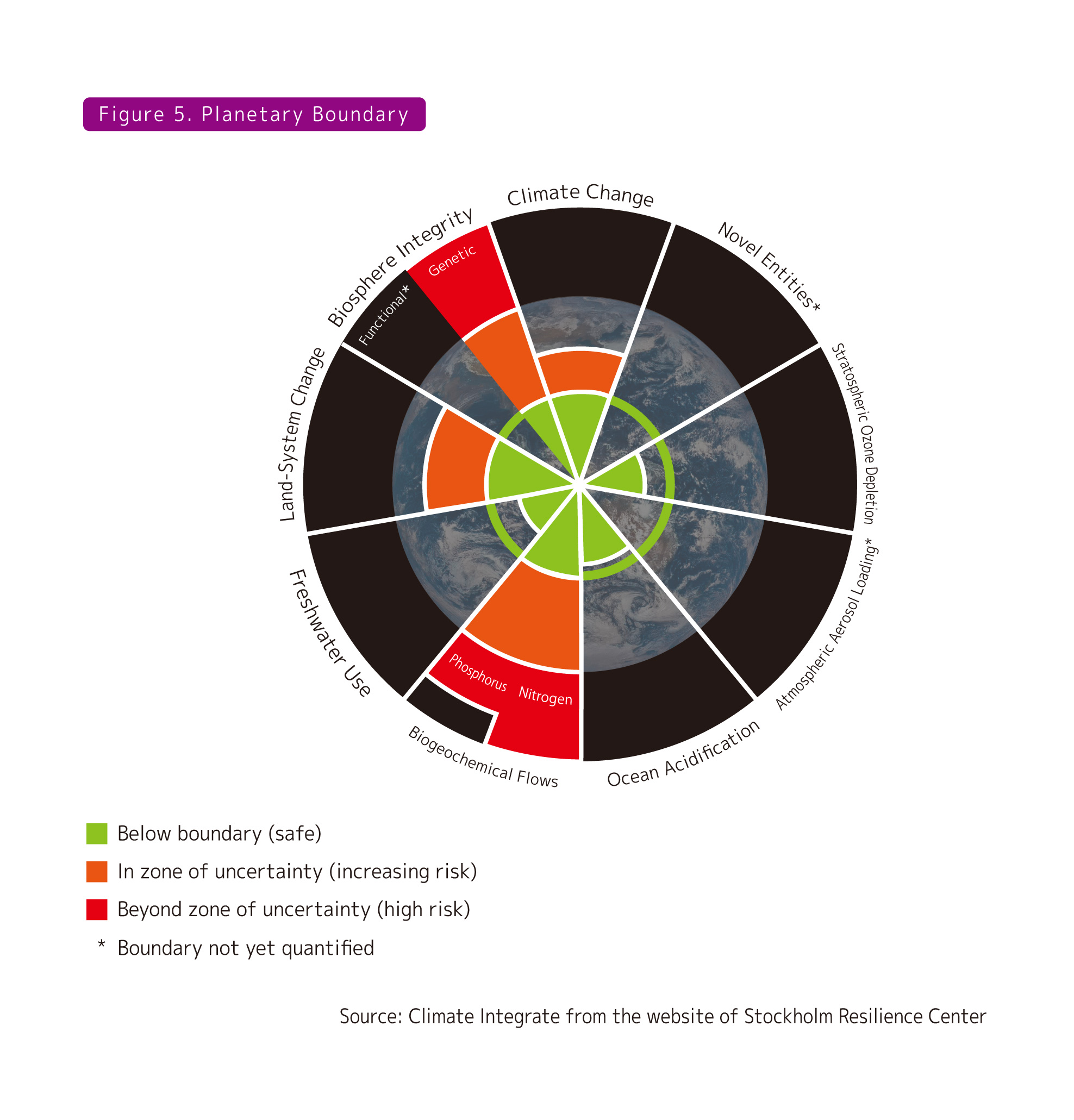

③Environmental impacts: Disruption of the nitrogen cycle

Unless properly mitigated, the combustion of fuel ammonia will release nitrogen oxides, which will exacerbate air pollution. As Planetary Boundary studies clearly show, increased nitrogen use will further interfere with the already-unbalanced nitrogen cycle by increasing nitrogen flows into terrestrial and aquatic systems, and have significant negative impacts on biodiversity, due to the expansion of “dead zones” where living organisms cannot survive.

* Planetary Boundary is a concept of boundaries that scientifically define the range within which the Earth can safely accommodate humanity activities. This concept was developed by Johan Rockström from the Stockholm Resilience Centre and others.

Transition to renewables

to decarbonize the electricity sector

As described above, even though little or no reduction in CO2 emissions can be expected by co-firing or 100% firing with ammonia, the Japanese government and private sector are moving toward a target of 20% ammonia co-firing in coal-fired power generation by 2030, claiming it contributes to decarbonization. Developed countries must complete a coal phase-out by 2030 in order to be aligned with the world’s target of limiting warming to 1.5°C. Contrary to this, the Japanese government’s policies mean Japan would continue using electricity generated from coal even after 2030, which conflicts with the 1.5°C target.

No CO2 emission reduction or cost-related advantages arise from large-scale investments into infrastructure developments for the use of ammonia. Because all of these projects involve environmental impacts, they pose significant risks. Conversely, it has been well-documented that the most cost-effective way to decarbonize the electricity sector is to make the transition to renewable energy generated from solar and wind power. That approach has huge potential. This paper has presented several of the reasons why Japan’s policies promoting co-firing with fuel ammonia for the thermal power generation sector need to be challenged.